The Diplomacy of the Village: Governance Without Bureaucracy

Precolonial negotiation as political technology

When we think of governance today, we picture big things: parliaments, paperwork, police, politics. But in precolonial Africa, governance didn’t always look like that. There were no ministries, no printed constitutions, no bureaucratic bottlenecks.

And yet — the villages held.

Conflicts were resolved. Land was shared. Power was negotiated. Authority was respected, but it was rarely absolute. Decisions were made in open circles, not behind closed doors. People found ways to live together — not perfectly, but meaningfully.

So how did that work?

Governance as Relationship

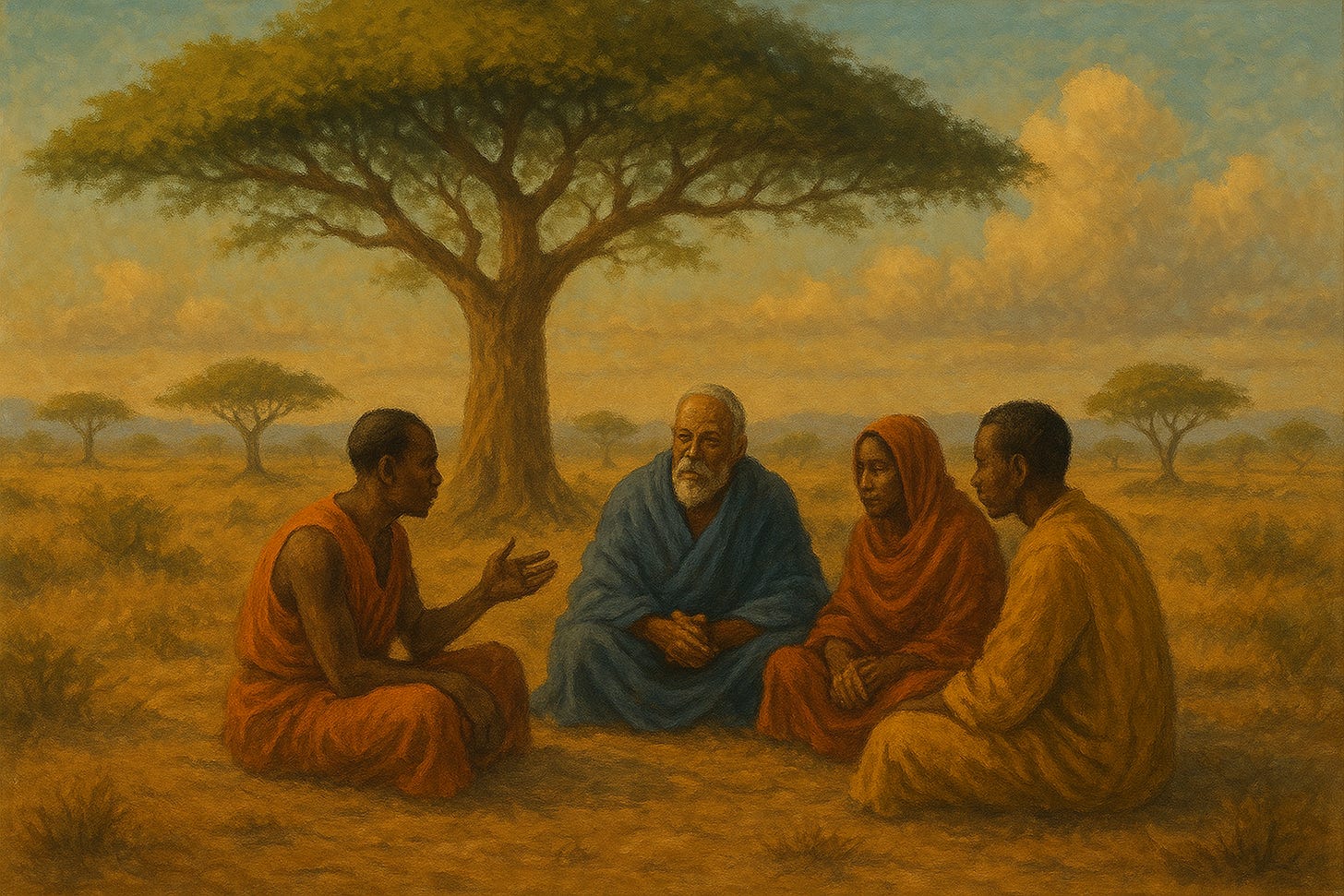

In many African societies, governance was not a structure — it was a process. It flowed through kinship, elders’ councils, ritual obligations, storytelling, and community memory. The power didn’t sit in a building. It moved with people. It was built on relationship rather than hierarchy.

When disputes arose, they weren’t just settled with law — they were resolved through negotiation. Through listening. Through an understanding that maintaining harmony was more important than declaring a winner.

This wasn’t weakness. It was technology — a form of political engineering.

No Bureaucracy, No Chaos

The absence of centralised government didn’t mean the absence of order. Many African societies used rotational leadership, federated clans, and seasonal councils. Authority was often distributed and conditional — you ruled well, or you stopped ruling.

That flexibility allowed communities to adapt to change. And it meant governance wasn’t something done to people — it was something they participated in, shaped, and inherited.

What We Lost

Colonialism brought bureaucracy. It introduced fixed borders, top-down command, and the rulebook approach to politics. But in the process, it dismissed the intelligence embedded in African negotiation systems.

It saw fluidity as disorder. It mistook consensus for slowness. It replaced dialogue with decree.

Today, we’re living with the aftershocks of that shift. And maybe it’s time to remember what came before.

What We Can Learn

What if governance didn’t need to be expensive, extractive, or inaccessible? What if our systems of power were designed to maintain trust, not just enforce rules? What if we built nations like we once built villages — around people, not papers?

The village, it turns out, was more than a place. It was a political philosophy.

And it might still have something to teach us.

Related reads:

The Thinking Savannah: Visualising Endogenous Innovation