The Mapmaker’s Mistake

Colonial Cartography and Identity

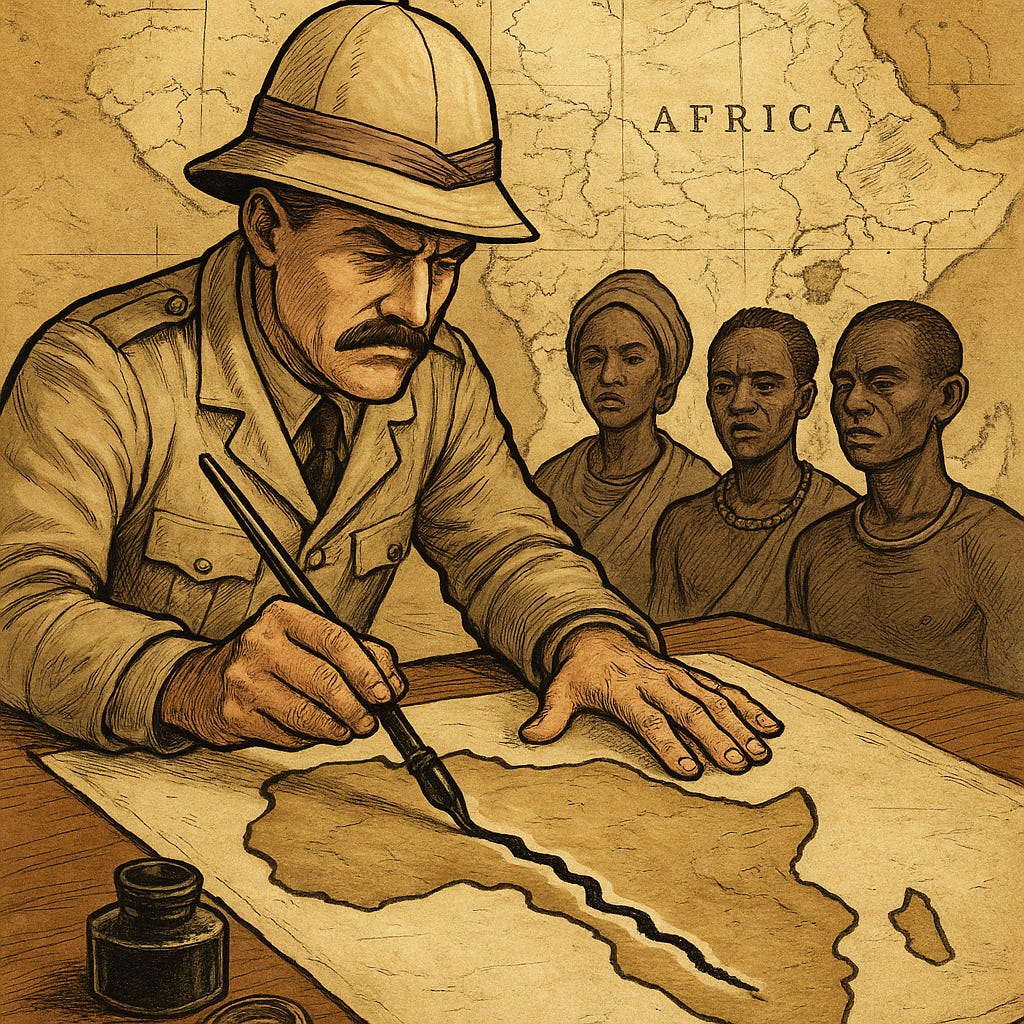

There are few things more dangerous than a bored cartographer with too much ink and not enough understanding.

By the late 19th century, the British Empire had perfected the art of naming what it didn’t know. They had measured the Nile, sketched the Zambezi, and were now busy assigning new identities to old civilizations — like a drunk wedding guest handing out nicknames to strangers.

Enter southern Africa, 1890s.

In marched missionaries with hymnals, administrators with census sheets, and explorers with compasses, all in search of souls, subjects, and sugar. They found people. Many people. Karanga, Zezuru, Ndau, Korekore, Rozvi, Manyika, Barwe, each with their dialects, customs, rainmaking ceremonies, territorial memories, and deep oral genealogies. Each with their own name.

But for the foreign pen, this was a nightmare. There were too many names. Too many variations. Too many voices speaking too many tongues that sounded just similar enough to confuse the ear but distinct enough to resist classification.

And so, the colonizer did what colonizers do when nuance becomes inconvenient: they made something up.

The term “Shona” begins appearing with casual confidence in British documentation in the 1890s. It is not a term sourced from the people themselves, it is a filing category derived from god knows where. A sorting hat for the colonial bureaucracy. A way to separate the “non-Nguni” populations from the “others” they already recognized, like the Ndebele. It was shorthand. It was laziness. It was power.

And if we’re being honest, it was also a bit like saying, “Hey you.”

Because that’s essentially how “Shona” began. As a placeholder. As a shrug. When you don’t know someone’s name, or worse, don’t care to learn it, you call them whatever helps you sleep at night. And for colonial administrators in Salisbury and London, Shona was just tidy enough to soothe the imperial conscience.

But names are not neutral.

This is where the Acacia Framework of The Thinking Savannah invites us to slow down. If identity is a canopy, it is because it is upheld by deep and layered roots. Every name, every clan, every dialect is a root. Every proverb, every praise song, every totem — a thread in the underground network of cultural nourishment.

So what happens when you cut the roots and staple a new name onto the canopy?

You get a tree that stands — but doesn’t remember where it grew from.

Shona became that label. And over time, through missionary schools and colonial censuses, it went from administrative convenience to accepted identity. A people began to believe the name they were given, not because it reflected them, but because it was repeated. By priests. By teachers. By the state. A foreign name grew local roots, not because it was planted, but because it was pounded into the ground with the weight of empire.

This is not a tragedy. It is a twist. A comic absurdity in the theatre of colonialism. Imagine entire ethnic groups — with proud lineages and sacred histories — being united by a word no ancestor ever spoke. A name that existed on paper before it existed in song. That is the mapmaker’s mistake: assuming that drawing a boundary or naming a people gives you ownership of their soul.

But the soul resists.

Even today, in rural homesteads and nighttime firesides, the elders still speak of mhondoro, not Shona gods. They speak of mutupo, not Shona surnames. They pray in tongues older than the term Shona itself. The canopy may have been renamed, but the roots... the roots are still whispering.

The danger is when we forget to listen.